Biomechanics of hallux valgus and spread foot.

Hallux valgus seems to be the hallmark of forefoot deformities. Its occurrence in the modern society has been estimated to be between one-tenth, one-sixth, and one-third of the population. It has also been noted to occur at least twice as often in women as in men. It has on several occasions been referred to as the “hallux valgus complex”, meaning that when it occurs, it is associated with a multitude of other symptoms or deformities of the forefoot. These include calluses under the forefoot, metatarsalgia, splayfoot, flatfoot, plantar fascitis, and hammer toes. Thus, in the study of hallux valgus one often must discuss all these other deformities.

Hallux valgus seems to be a deformity that was uncommon until the wearing of fully enclosed shoes and boots.

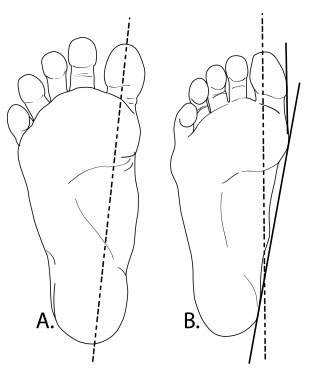

(A) A foot that has never worn shoes. (B) A normal foot that has worn shoes. Feet that have never worn shoes are commonly found to have the digits in alignment with their respective metatarsals, giving the foot a fan shape. Normal feet that wear shoes are commonly found to have the digits in alignment with the longitudinal axis of the rearfoot, thus giving the foot a sarcophagus shape.

From the fact that the deformity occurs mostly in the shoe-wearing population, and that women tend to wear pointed-toed, high-heeled shoes, the most obvious conclusion would be and has been that wearing misfitted, pointed-toed shoes is the primary etiology in initiating hallux valgus.

(A) When the hallux is in an abducted position, the pull of the flexor hallucis longus (Fm) creates an abduction moment around the vertical axis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MO. It also produces a compressive force within the first metatarsophalangeal joint (Frm) and a friction force against the ground (Ff). (B) The equal and opposite force of Frm (labeled Fjh) and the compressive force in the first metatarsocuneiform joint (Frjh) combine to create an adduction moment of the first metatarsal (M2), which would increase the first intermetatarsal angle.

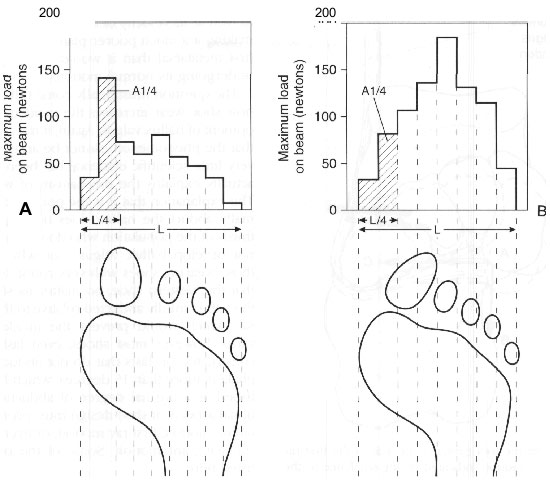

Peak loads recorded across the forefoot in a typical normal and a typical hallux valgus foot. (A) In the normal foot the first metatarsal bears approximately twice the peak load as any of the other metatarsals. (B) In the foot with hallux valgus, there is a loss of weight-bearing load by the first metatarsal and transference of peak loads to the second and third metatarsals. This produces a callus formation under the second and third metatarsal heads because of the increased weight transference.

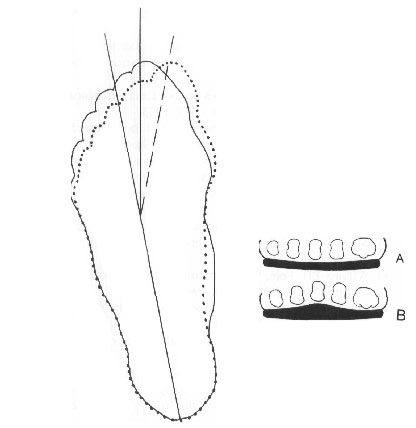

(A) An adducted forefoot type (solid line) that is placed in a straight last shoe will pronate in the rearfoot to place the forefoot in a more rectus position (dotted line).

(B) It is also noted that most shoes are built on the inside with the area under the central metatarsal heads lower than the surface under the first metatarsal head. It has been hypothesized that this may also contribute to abnormal dorsiflexion of the first metatarsal inside the shoe.